Chapter -a

CHAPTER A: "I WAS JUST A LITTLE GIRL"

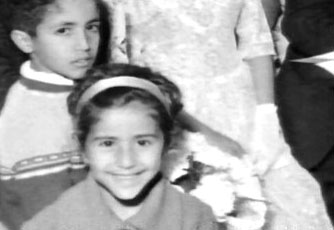

Bat-Sheva Haza was born on Tuesday November 19th, 1957. She was the youngest daughter in a family of seven daughters and two sons. Her father was Yefet Haza and her mother was Shoshana Haza. She was the sister of Yehuda (the eldest), Noga, Eti, Rachel, Yardena, Zehava, Shuli and Yair. Her mother was a housewife and her father was a simple worker in Tel-Aviv municipality until he retired. Her parents immigrated to Israel from Yemen on 1944, “with the strongest desire to come to Zion Jerusalem”, according to what Ofa said. In Yemen, Yefet was a workman on a ship. Once, while he was sitting in a restaurant in Aden, he was told by one of the waitresses that she had a sister who was single. “Bring her here and I’ll marry her”, said Yefet. Shoshanah, the daughter of Shlomit Abdar, was immediately brought on a donkey and they both married without knowing each other.

In 1944 the Haza couple had decided to immigrate to Israel. They sailed by ship to Egypt and from there came to Israel by train. After a short time of adjustment in Atlit, Haifa and Hadera, they moved to Hatikva neighborhood in Tel-Aviv.

“When my mother was pregnant with me, she had a tiny round belly even in her last months of pregnancy. When she felt that it was time she obviously rushed to the hospital. The doctor took a glance at her tiny belly and couldn’t believe her time had come to give birth. Therefore he sent her home. But my mother, who was a midwife, knew better. She seated herself on a stretcher in the maternity corridor and that’s how I came into the world. My parents decided to call me Bat-Sheva (in Hebrew: the seventh daughter), because I was the seventh daughter in our family, and therefore I was registered as Bat-Sheva. But my elder sisters didn’t like the name. They insisted that my name would be Ofra. My parents gave in and since then I’m Ofra”. At the age of six, Ofra changed the name officially in the ministry for interior affairs. “The family name – Haza – was derived from the name of the village in Yemen where my parents lived. The name of the village was El Haz, and our family was the only Jewish family in the village”.

“She was the light of the house” said Shuli, Ofra’s sister. “She was an amazing baby, very beautiful. We were sleeping together, that’s why we are so attached to each other”.

“I had an incredible childhood. I was the youngest – the ninth child of the family’s children – and everybody spoiled me. My father, my mother, my elder brothers and my six sisters. Altogether, my family is terrific; they love each other, support one another, and they are united and spend much time together.

“I was a very skinny child, short hair, shy. But all along I insisted on one thing – I wanted to be a singer.

“My home was definitely the source of my singing desire. Everything comes from my mother, who was a well-known Hina’s singer, who used to sing at many Jewish Yemenite occasions in Israel (weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, etc). When my parents immigrated and settled in Hatikva neighborhood a regular custom developed: Every Saturday night my mother was sitting with a side drum on the porch and all the neighbors and relatives used to come to listen. Mother used to sing original Yemenite songs and everyone used to sit around her fascinated, singing, eating ‘Ja’ale’ and drinking coffee. This custom remained for many years. Additionally, my mother sang songs almost everyday at the kitchen, beside the stove, during laundry and washing the floor. So it was not just on holidays and Saturday nights. This is how the music penetrated our life as a matter of course.

“My mother says that when I used to cry in my infancy she didn’t come and soothe me immediately. ‘I wanted her throat to open up’, she said. And indeed my throat opened up, and so from my earliest memories I am singing. I used to sing all the time – at first in the innermost parts of the house, in the bathroom, standing in front of the mirror and singing. I listened to the radio and sang – imitating singers. I began to collect song lyrics, I filled entire notebooks. My favorite singer was Ester Ofarim.”

“Ofra was singing all the time”, says Shuli. “She used to sing in front of the mirror, or to tables and chairs, singing and talking with them. Suddenly I would hear Ofra singing a song about the stars and the sky, a song I wasn’t familiar with and never heard before, and I would ask her: ‘Ofra, what are you singing’? And she would say: It’s a song of my own, I wrote it by myself’.

“She drove me mad with her wish to sing”, says Shuli. “‘Shuli come and give me an audition’. So I told her: ‘all right, stand up’. She would stand and I was her audience of course, and when she finished singing she used to smile a certain smile like she was asking: ‘How was I, Shuli?’ I told her: ‘You are great, we’ll do everything so you’ll become a singer’. And I used to hug her and kiss her”.

Ofra studied in “Uzi’el” in Hatikva neighborhood. “Then I was discovered at school. We had a little choir and I was the soloist. A very popular song at the time was ‘Yerushaylim Shel Zahav’ (‘Jerusalem of Gold’), and I used to prolong the last bar at the end of the song: ‘Halo Lechol Shirayich Ani Kinor, Kinooooor’, with the flimsy voice I had then, and everybody would be thrilled about it”.

“My brothers and I had a record shop in the center of the Hatikva neighborhood”, says the producer Asher Re’uveni. “On her way from school Ofra used to sneak inside and beg: ‘Please, please let me hear Ester Ofarim’. She used to close her eyes, listening to the song and being carried away with the music”. Shuli remembers how Ofra asked to go on stage in a young talents contest hosted by Rivka Micha’eli in Hatikva neighborhood. “I want to go on stage and sing”, demanded the young girl, but the line was already long and others already took her place.

Around the age of 11 and a half, Ofra began to take a part in the choir of Menashe Lev Ran. She was then in the sixth grade, traveling to the big city every week to “Beit-Berger”. When she was twelve and a half in the summer of 1971, she agreed to sing in a friend’s wedding, and here for the first time she was heard by Moshe Arusi, who was a member of the Hatikva Neighborhood Workshop Theater. Bezalel Aloni, a young man at the age of 29 who had just begun as a writer, was the man who set up the Workshop. Since no instituted theater would agree to show the protest play he wrote called “Plastic Flowers”, he decided to organize a group of actors on his own and produce the play independently. “The idea was to bring up protest plays with actors from the neighborhood, and thus to discuss and clarify their daily problems”, said Bezalel.

Bezalel was born in Petach-Tikva to a family of ten children. Three of them passed away. Bezalel was a baby when his parents left Petach-Tikva for Hatikva neighborhood. Three of his brothers were excellent football players in “Bnei Yehuda”. “Most of my education I’ve acquired from the street”, says Bezalel. After he was released from the army artillery, he became a drama coach for street gang. “I’ve always had an ambition to go on stage”, says Bezalel. “At the age of 15, before I was recruited to the army, I hosted radio shows for Yemenite immigrants. I was a prodigy. I hosted radio plays and acted in a few theaters”. Later, Bezalel published a book of his poetry.

In Ramot Yisrael neighborhood Bezalel set up a dramatic circle called a “Workshop”, which dealt with problems which bothered youth in distress. “At the first show we produced, inspectors from the Tel Aviv municipality came and reproached me: ‘We pay you to produce shows for Purim and Passover and not stuff like that'”.

About ten years later Orna Porat and Chaim Shiran established the Hatikvah Neighborhood Theatre Workshop, as part of their project to establish theater groups in poorer neighborhoods. A short time after the workshop was set up Shiran travelled to France, and Porat also left the project. Bezalel replaced the two and began to run the workshop.

The workshop was both an independent framework and was financially independent. “We then consisted of just Ogenia, my wife, and I, a young couple with a cute little son, and if the workshop needed money I took it out of my own wallet and gave it to them”. Bezalel lived at the time with his wife and little boy in housing for young couples near Hatikva neighborhood. The workshop had quite a radical character, at least in comparison with other cultural neighborhood. “Tzavta” was their home theatre. The workshop had significant success. At the time, review articles in the press showed the media to be greatly interested in the workshop. Sometimes the social interest was stronger than the artistic one. Basically, the workshop moved the conscience of the media and society to greater awareness of the problems of the slums.

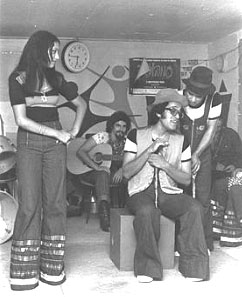

“Moshe, the guitar player, told me: ‘Michael, there is a sweet girl who sings beautifully’, says Michael Sinu’ani, another member of the workshop. “I said: She’s welcome”. “I won’t forget the first time she opened her mouth and sang the song: ‘Shecharchoret’ (‘Dark Girl’). We all felt a chill going through our back. I told Bezalel: ‘Listen, we have a sweet girl at the neighborhood who sings adorably’. He told me: ‘bring her here'”.

Ofra claimed back then that she didn’t know about the Workshop’s existence at all, which at the beginning had done most of its rehearsals in the cellar of Bezalel’s house. Michael Sinu’ani offered Ofra to join the workshop. She hesitated, but at last agreed to come to a meeting at Bezalel’s house, a meeting that changed the life of both of them.

“I came to Bezalel’s house, and because there wasn’t much room we sat in the kitchen” remembered Ofra.

“My wife Ogenia and I were in the middle of our lunch hour when a child at the age of 12 and a half arrived at our kitchen dressed in her junior high uniform”, says Bezalel.

“What can you do?” asked Bezalel of the skinny little girl with the pigtail who came to him.

“I know how to sing”, said Ofra. “Please sing”, said Bezalel. “At the time I adored Edna Lev” says Ofra. “I started singing the song ‘Im Tashuv’ (‘If You Come Back’)”. But Bezalel stopped her. “You have a very beautiful voice, but don’t try to imitate Edna Lev. Sing at your natural style”, said Bezalel.

“I didn’t fully understand what he wanted from me, but I sang”, says Ofra. “Her voice made me shiver” remembers Bezalel. And then he decided at once: “Come to the rehearsals!” Her joining the workshop was actually the thing that paved her way to the stage.

While Ofra got the chance of her life from Bezalel, it was Shuli who convinced their parents to let her be a singer. “I fought so our parents will let her sing. They agreed on one condition: ‘If she sings, you have to go with her and take care of her’. She was only 12. Our mother babysat my babies, and I went with Ofra to every performance. I was always with her. My parents liked Ofra’s singing very much, but there was a problem with Fridays (religious Jews do not perform on Friday evenings). At first we didn’t want them to know that she was singing on Fridays, so I would sneak her to my house to baby-sit my children in the pretext that I had to go out”.

Even after she was accepted to the workshop she spent more than half a year acting only in minimal roles. Her first performance on stage was in the play “Plastic Flowers”. Ofra was a replacement actress and her part amounted to two words: “red carpet”.

“At the first show I let her say only two words”, says Bezalel. “At the second show she was replacing the stand-in actress, and that’s why she didn’t participate”.

Then destiny interposed.

A main actor at the workshop decided to retire exactly on the first night’s premiטre in “Tzavta” hall in Tel-Aviv of a play called “Sambusak, Matay Habchirot? (“Sambusak, when will the elections take place?”). “It was a guy named Mickey, who was a talented entertainer but not with a strong personality”, says Bezalel. . “Four hours before the premiטre he called me and said: ‘I’m leaving the workshop’ and hung up the phone. At that time Ofra was present in every rehearsal and she knew all the roles. I said to my wife Ogenia: alert Ofra quickly come to ‘Tzavta’. And she came. She brought slippers from home and her mother’s robe, went on stage and succeeded without rehearsals to transform the role from that of a male to a female. She captured the audience”.

“Ofra was the younger daughter in a traditional old-fashioned Yemenite family. She and her parents didn’t share many things in common”, says Bezalel. “All her bothers and sisters had already moved out, except for one brother, Yair, who was still at home, and he didn’t really get along with her then. There were brothers’ quarrels, like in every family. Actually she had nobody to speak to at home. I would go there every evening and get her out of bed for rehearsals or performances and tell her parents: ‘Don’t worry, I’ll watch her’. At a certain stage she actually moved out and came to live at my house and she had a room of her own in our home”.

“Bezalel would give us some money and we used to go out and spend it in the central station”, said Zehava Tovim, another member of the workshop. “If we bought some clothes, Ofra would say to the seller: ‘Give me a discount, please, please, my name is Ofra Haza, remember my name, I will be a famous singer one day’, and sometimes it worked”.

“When she was 14”, says Avihu Medina, who composed a few of the workshop’s songs, “she surprisingly announced to me that she would withdraw from any further artistic activity and that she wouldn’t sing nor act again”. “My parents stopped my participation at the workshop because they didn’t approve of my school progress”, said Ofra. “I didn’t agree with her and did almost everything to convince her to return to the workshop”, says Medina. “I composed for her the song “Ga’agu’im” (“Longing”), her first solo. I promised to watch her and follow her return to the stage. After much persuading she agreed to come back to the stage”. Bezalel also convinced her parents that she was in good hands and insured that her performances wouldn’t interfere with her studies. “After every show I would hurry up and drive Ofra home to enable her to get up to school in the morning”, said Bezalel.

“The ‘Yom-Kippur’ war stopped the continuation of the protest show produced then”, remembers Bezalel. “Immediately we came up with another new show, ‘First Love’, which was dedicated to the stories of the immigration of the Yemenite Jews. Ofra, with the hit ‘Ga’agu’im’ (‘Longing’), was our star”. Together with the workshop Ofra went to give performances in Sinai in the Yom Kippur War. “I felt that we made an important contribution to the morale of the soldiers”, said Ofra. “Every performance was a rich experience. They asked me if I were 18 or 20, and said I reminded them of their home. A few times we were very close to the bombs. Our performances were shifted from place to place, and we had helmets on our heads. In the middle of a show opposite Cantara we witnessed an Egyptian plane being shot down. After a recess we continued the show as if nothing happened”.

“Ofra’s ability to adjust to the battlefield conditions amazed me, with all the movements, the heat, the sand and the battle portions”, says Bezalel. “She surprised me with the maturity she expressed there, especially at how she made the tough guys with the ranks on their shoulders happy”.

The members of the workshop recorded the songs of the play, including Ofra’s solo song “Ga’agu’im” (“Longing”). The song was heard on the radio and the announcer said: “And now Ofra Haze (in Hebrew: chest) is about to sing the song “Ga’agu’im” (“Longing”). “Haze? Haze (in Hebrew: Chest)? Why are they doing it to me?”

“Never mind, calm down” said Bezalel. “You’ll see, they will learn how to spell your name correctly in no time”. And that’s how it was: after a short time the song climbed at the top of the charts.

In 10th grade Ofra moved to “Ironi Chet” high school (City High School #8) in Hatikva neighborhood. “I remember I was quite a good student at high school in ‘Ironi Chet’, says Ofra. “I especially liked my classroom teacher, Bracha. She taught me history and geography”. About the same time Ofra was a member at the “Hano’ar Ha’oved Vehalomed” (a scouts’ movement) in Hatikva neighborhood. But there was a time conflict between school and the Workshop’s performances, and Ofra realized that she had to choose. “As a student at a religious school, I couldn’t go on with my career”, says Ofra. She left high school and went to study in Mishlav high school, where she accomplished external matriculation. “It was very hard to combine studies and performances”, says Ofra. “I would study for my matriculation exams during my long journeys to the shows. In fact, I passed all my matriculation exams with Bezalel’s help. He helped me study. I remember that on our long journeys we would punctuate the signs on the road for my grammar exam”.

In 1974 Ofra took part in the Oriental Songs Festival with the song “Shabat Hamalka” (“Saturday the Queen”), and won third place. “For the first time in my life I performed on T.V. and on a live broadcast. What an excitement it was. Bezalel bought me a black ornate dress, and the funny thing was that I was still so ‘green’ (inexperienced) about everything that I even forgot to prepare shoes for the festival, and at the last minute I had to borrow a pair of wooden clogs from my mother”, said Ofra.

“It was very quick, as simple as that, but it made all the difference”, remembers Bezalel. “After Ofra won the Songs Festival her brothers wanted her to take part in events like weddings, Bar-Mitzvahs, etc. I had already told her: ‘You need to choose between the workshop and the other singing events’.” She decided to stay at the workshop and since then our destinies were interlaced”. Ofra took lessons in voice training, dancing and motion and of course more and more performances in front of a crowd. “All my life I dreamt of becoming a singer, and now it finally came true. It was a shock, it was amazing, and I couldn’t be happier”.

Ofra recorded three long playing records with the workshop. “We protested in a civilized manner in the theater, which actually was our home theater ‘Tzavta’, but we also performed in kibbutzim, high schools and universities. “I didn’t fully understand the nature of the Hatikva workshop then, which was determined by its founder and manager, Bezalel. I didn’t understand because I was a kid. I was born, grew up and brought up in the neighborhood. I didn’t know any other reality. But as time passed and after the five productions I had as a singer-actress — ‘Prachim Miplastic’ (‘Plastic Flowers’), ‘Chashud Tamid Chashud’ (‘A Suspect Always a Suspect’), ‘Sambusak, Matay Habchirot?’ (‘Sambusak, when will the elections take place?’), ‘Vechutz Mize Hakol Beseder’ (‘besides that everything is all right)’ and ‘Shir Hashirim Besha’ashu’im (‘Song of Songs in Amusements’) — I absorbed a different kind of material, from a different world, which helped to form my personality and my way of thinking. Material that I didn’t get in school: social problems, education, crime, poverty. And that was the best school I have ever had in my life, for seven years, and without the support of the ministry of education or Tel-Aviv municipality. It was simply the private obsession of Bezalel to make theater, to make a protest in a civil way”.

“Because of this theater other theaters started to pop up in other places, but there were no theaters like ours, because we were the pioneers who put our souls into it. The workshop members were from the neighborhood, not famous nor professional, and they were adults, I being the youngest one in the workshop. From my first moment at the theater I knew that I wanted to become a singer, and it came up in a very natural way. I studied there, I developed, I grew up”.

Gradually, Ofra’s roles at the shows and workshop recordings started to grow. “I can’t say I didn’t feel a little pinch in my heart”, says Sinu’ani. “Such a small girl, a teenager, and I am already well known and famous, and she takes most of my songs. I came to Bezalel and asked him: ‘What is going on, Bezalel? Up until now we would split equally or I got a little bit more’. He said: ‘That’s how I want it to be’”.

In 1975 Ofra took part with all of the workshop members in the Songs Festival with the song “Parashat Drachim” (“Crossroad”), but they didn’t win the first prize. At about the same time Bezalel paid for Ofra’s driving lessons. Bezalel was proud of her because she got her driver’s license on her first try, after only 10 driving lessons.

At 18, Ofra went to the U.S.A. with the show “Kan Yisrael” (“Israel Is Here”) with other singers too, in a coast to coast tour, on behalf of the foreign ministry. For three months the Israelis danced there, “and I was the only dark skinned one. However, my Yemenite songs, which came deep from the bottom of my heart, left a very strong impression”.

Despite the strong impression that the workshop activity left, Bezalel realized that the real future belongs to the soloist, and he gradually started to pave her way towards an independent career. At that time – the middle seventies, the one who knew best how to build a singer’s career was Abraham (Deshe) Pashanell, the legendary producer of the “Hagashash Hachiver” (“The Pale Pathfinder”– an Israeli entertainment grou.p)

“Bezalel called me and said he was ready to put on a workshop show just for me”, said Pashanell. “That show was in the hall of Kibbutz Shfayim. I remember how I got there and saw Ofra on the stage for the first time. This one show was enough to realize she was an outstanding singer”.

“Almost a decade before, I played the potter’s role, Aliza Azikri’s father at his musical show ‘Nasser A-Din’”, says Bezalel. “Very soon I found out that I belonged to the back stage more than to the front stage. I invited Pashanell to the dress rehearsal of the ‘Shir Hashirim Besha’ashuim’ (‘Song of Songs in Amusements’) in Shfayim. He was fascinated by Ofra, took me aside and said: ‘Listen, she is worth millions. Let’s make a deal.’ I called Ofra. She did not agree to a five year contract”.

“She had a job integrity that even in the terms of today or the terms of the past, was rare to find”, says Pashanell. “It was obvious she was a serious girl who was given a good education, who knew how to work. The relationship between her and Bezalel was a thing I had never seen before, and I had seen a lot. His devotion to her and on the other hand her trust in him, were amazing”. Pashanell said that he was very much interested in her and he didn’t give up the contract. “He released her from the contract in ‘Isra-Disc’ and they signed a five year contract”, says Bezalel.

But there was a small obstacle – the army. In February 1976 Ofra joined the army. Many told her she’d better declare she was religious and wouldn’t be drafted (in Israel religious girls do not have to be drafted if they don’t want to), but Ofra refused. Her parents also supported her military service. “This is our country, and we are obligated to defend it”, says her father. Ofra claimed that she wanted to give her share to her country with all her heart, but the army treated her pettily, maliciously and played dirty tricks on her. After she finished her basic training, and based on her stage background, Ofra was

sent to a band called “Tzevet Havay Hanachal” and later on to the “Lahakat Hasadna Hagayasit” (both are military bands). But she didn’t find her place in either of them.

“Nothing serious was done to use my potential”, said Ofra after she was released. “I was given a producer and an accompaniment band and they sent me to sing the same materials that I had from the time of the workshop. No new materials, no good treatment nor nurture. For some time I wandered around the army posts and I wasn’t pleased. I felt it wasn’t a professional show. I knew that I would have enough time to perform for money in the outside market, and I requested to do a regular job. I served as company clerk in an armored division. I liked this part of the service very much. The soldiers loved me. They treated me wonderfully. In the evenings I would go to the theater and participate in the workshop shows”.

Ofra passed her military service in recruiting army reserves and releasing them at the end of their service.

After only one year in uniform in which she also took part in the workshop’s activity all along, the army accepted Ofra’s request to shorten her service to allow her to work and earn money to help to support her parents. Her mother, Shoshana, became ill at the time, and the service conditions officer that was sent to see the family was convinced that Ofra’s presence at the house was necessary.

Bezalel himself made what he called afterwards “the decision of his life”: to leave the Hatikva Neighborhood Workshop Theater and devote himself to managing Ofra’s career. This decision in fact put an end to the existence of the workshop, which without the man who stood behind it didn’t survive long. “It was a loss for Israeli Society” claimed Bezalel after the workshop was shut down. “I went to qualified institutions and proposed that they take over the workshop management as a project which already had healthy foundations. But nobody wanted to take it. I did five productions at the workshop. I felt I had fulfilled my potential, and that I had nothing to contribute to it anymore. I wanted to devote myself to Ofra. At a certain point, Ofra outgrew the workshop. At first I used the workshop as a stage to convey messages of protest, but then gradually it became Ofra and the workshop. She gradually became the center, the main interest”.

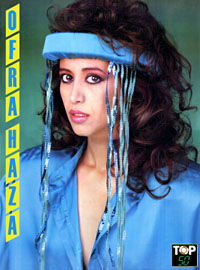

As a part of the new changes in her life, Ofra decided to undergo a small plastic surgery in her nose. “It was a small surgery that Ofra had undergone before she started to get requests to play in movies. Dr. Shulman, the surgeon, said that maybe there was no need to operate because her face is perfect”, remembers Bezalel. “However, he removed a little bit from her nose. And if she was naturally beautiful in my eyes beforehand, now she became even more beautiful”.

Ofra’s first significant step after her release from the army, and under the supervision of Pashanell with Bezalel as her personal manager, was to go back to the ensemble form. In those days Yardena Arazi withdrew in turmoil from the threesome “Shocolad, Menta, Mastik” (“Chocolate, Mint, Bubblegum”) and Le’a Lupatin quickly withdrew after her. Pashanell decided to create a new ensemble. To Ruthi Holtsman, the only one who was left from the original ensemble, he added Israela Kriboshe, and Ofra was made the third member. In order to let the new ensemble run with a minimum of local exposure, it was decided on a six week Scandinavian performance tour.

“When Pashanell told me he was looking for a singer, I didn’t know he wanted a singer for a threesome”, said Ofra in an interview. “But when I realized what it was all about I was happy. It’s a hard work, but it gives one a chance to perform new materials that one hasn’t done before, and there will be performances abroad. It’s an excellent school”. But the reality was different. The new ensemble “Shocolad, Menta, Mastik” (“Chocolate, Mint, Bubblegum”) completed their performances in Scandinavia, but came apart before the local audience had a chance to see them. “On the journey itself I had already felt it wasn’t what I had expected it to be”, explained Ofra two years later. “Each one of us had a different mind. We weren’t attached. Everything was done in a rush. I called to Bezalel and Pashanell from abroad and siad I felt I should be a soloist, and there was no way I could be a part of a threesome. Luckily, they showed empathy and said: ‘never mind, nothing happened’. On the whole it was a good try”.

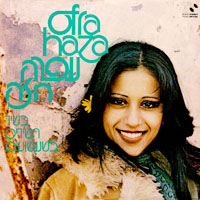

Ofra released her first solo Album “Shir Hashirim Besha’asuim” (“Song of Songs in Amusements”) which was published on “Isra- Disc”, “but the real thing didn’t happen yet”, says Bezalel. The album wasn’t a “personal album” of Ofra in the full sense of the word. Many of the album songs were sung by the Hatikva Neighborhood Workshop Theater, and also the name of the album was called after one of the workshop’s performances. The songs themselves sounded identical to those Ofra sang together with the rest of the workshop members. The album wasn’t a breakthrough.